Click here to download the SHIp Initiative booklet

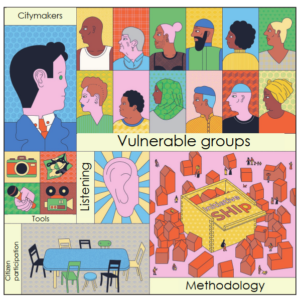

SHIp Initiative – Safe, humane and inclusive public spaces

When citymakers embark on a mission to make public spaces safer, they generally tackle crime: How do you make crime harder to commit and easier to detect? And this often means fortifying public spaces, stepping up surveillance, or even restricting access to or use of certain areas. Ultimately, public spaces become hostile to vulnerable populations such as women, racialized people, children.

The SHIp initiative stems from Edna Peza’s research into the link between public spaces, feelings of insecurity and everyday practices.

The SHIp initiative is an introductory guide aimed at citymakers who want to make public spaces safer, more humane and inclusive, by placing vulnerable groups at the heart of their approach.

The SHIp initiative challenges current planning practices and citizen participation, i.e. the dominant discourse around city-making, which focuses on making public spaces less criminogenic but not necessarily less violent.

Here are the key concepts guiding the SHIp initiative:

1. Feelings of insecurity vs. fear of crime

Crime is one component of city dwellers’ sense of insecurity. But it is not the only factor.

Violence (direct and structural) is at the heart of this project.

Not all crime is violent, and not all violence is crime.

To deal with safety in public spaces and the way city dwellers perceive these issues, the feeling of insecurity is a more solid concept than the fear of crime:

Crime is just one of the many elements that can lead citizens to have a negative perception of their environment: low crime does not necessarily imply a positive perception of safety, even less so for vulnerable populations.

Fear is not the only emotional reaction an individual may have to crime or violence – especially those from vulnerable groups who face structural and direct violence in their daily lives in public spaces.

Feelings of insecurity are influenced by environmental characteristics, gender, age, social representations of dangerous places, community ties, attachment to place, daily experiences, perceived vulnerability and so on.

2. Intersectionality and vulnerability

Victimization is a dynamic process, influenced by gender, age, socio-economic status and so on. The failure to take account of social phenomena – such as racism, sexism and classism – has led decision-makers to consider that negative perceptions of safety are exaggerated by hypersensitive individuals.

Vulnerable groups have a heightened awareness of violence, an awareness that involves more nuance and detail than crime statistics.

The normalization of violence is a phenomenon often ignored in analyses of public space. Yet it is a feeling that is often present in individuals who have no choice but to be confronted with violence on a daily basis.

For example, a person who has never visited a “violent” neighborhood may express a strong fear and desire to avoid it at all costs.

On the other hand, an inhabitant of such a neighborhood has a more nuanced perspective: without having much choice about how to get out of it, and knowing that the authorities are no help, he or she might say that “it’s not that bad”, while being aware of the actual situations with greater precision.

3. Citizen participation and Socio-spatial transformations for safer public spaces

Those familiar with the “broken windows theory” are already aware of the link between the physical appearance of a space and safety. However, making public spaces safe, inclusive and humane for vulnerable groups goes far beyond placemaking.

For actions to be sustainable, they must be the result of participatory processes. They may occur spontaneously, but it’s best to make them part of the process. Otherwise, any impact they may have will be short-lived.

However, vulnerable groups are often less inclined to participate in such processes, because they feel they are being ignored. Collaboration with informal groups and local authorities is essential to build trust, encourage participation and achieve sustainable results.

The participatory processes put in place must guarantee inclusion and respect. The citymakers who carry out these actions must be sensitive to issues of inequality. City dwellers must be involved from data collection through to the production of solutions.

Empirical knowledge of city dwellers is essential to understand, for example, why they might feel safe in an area with a high incidence of crime. As for specialists, their knowledge and sensitivity are invaluable in “translating” these experiential ideas into viable actions.