Presented on the Journal of Public Space webinar, 6 August, 2020.

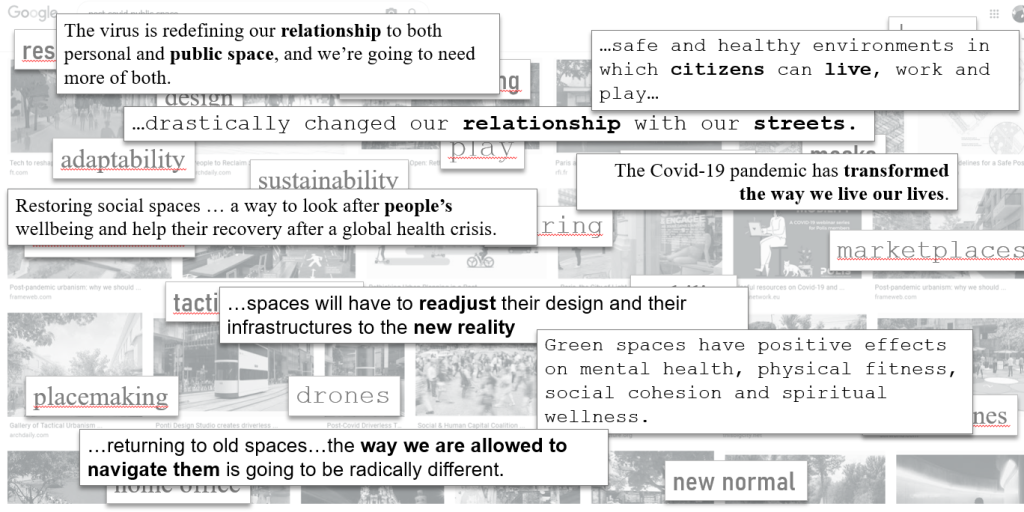

There’s been a lot of talk about the future of cities and COVID-19. A simple Google search for “post-COVID public spaces” will show us results about adapting the world to “the new normal”: to summarize, we are talking about design, smart cities, technology, sustainability, masks, restaurants, bicycles, tactical urbanism, etc.

Also, a lot is said about how we are now realizing how vital public spaces are, how necessary it is to adapt our lives to the “new normal”, about how our lives have changed.

Google brainstorm of post-COVID urban futures

A question then arises: what lives are we talking about?

The dominant discourse of COVID 19 and cities is built around a singular narrative, assuming the crisis has been more or less the same. It establishes an ongoing story in three acts: Business as usual, disruption by a lock-down revealing empty streets and transformed routines, and a gradual return where we are rethinking the role of public spaces (as depicted in this composed image of the Arc de Triomphe before, during, and after lock-down in Paris).

Three-act structure and an iconic Parisian street: les Champs-Elysées

However, the Champs-Elysées is not every street in France (or even Paris), Paris is not France, and this three-act narrative is not the global narrative of urban life in a health crisis.

This discourse fails to take into account other street lives and urban cultures that exist for a large part of the world and the most vulnerable populations, who are dealing with the hardest aspects of the pandemic. Due to economic and social inequalities, other ways of organization of everyday life in public space already took place way before the COVID-19 crisis, and for these sectors these three acts didn’t happen as neatly, if they ever happened.

For some populations, COVID-19 measures didn’t imply a change, but only another constraint to deal with, along with preexisting complications of street life.

For some, public space was never accessible, inclusive or safe to begin with.

Others already used public space for more than leisure out of preexisting needs.

The pandemic, along with lock-down measures, exacerbate ongoing structural inequalities (class, race, income, gender).

We can observe this at a micro level (individuals that coexist in any given city) such as women, informal workers, racialized individuals, the elderly, essential workers, and homeless individuals. And at a macro level, at countries of the Global South.

Women, the pandemic, and public space

Women have a very poor perception on security on public space, due to sexual remarks, touching, rape, gender related killings. Conditions of everyday life in public spaces such as poor lighting, low pedestrian traffic, and walking alone present greater risks.

Where lock-downs were enforced, activity on the streets dropped drastically during the day, and streets were desolate at night (except for informal workers). Some streets turned off public lighting since there was no activity outdoors. In some cities, connectivity in public transit networks was reduced, which represented longer distances of walking on empty streets.

Moreover, new empty spaces blossom due to businesses closing during and after lock-downs.

Thus, sexual violence in public spaces didn’t stop during the crisis. Cases in Chile, UK, Canada, Nigeria, Kenya, the Philippines, India, the US, France, and Mexico have registered cases of sexual violence against women: Exercising outdoors, working in public work settings, living in the street, traveling to and from work, such as essential workers –female doctors and nurses have been harassed, verbally and physically attacked or denied access to public transportation– and informal workers who couldn’t afford to stop working. This is especially significant when we consider that female informal workers, account for 95% in South Asia, 89% in sub-saharan Africa, and 59% in Latin America and the Caribbean.

In late June, UN Women published a brief that addressed the matter of gendered violence amidst the crisis titled “COVID-19 and ensuring safe cities and safe public spaces for women and girls” which is available here.

New crisis and old urban issues in the Global South

Lock-down and social distancing have proved to work in diverse contexts as measures to prevent the spread of the disease. Certain conditions facilitate following these protocols, such as:

- Housing (mostly formal)

- Clear differentiation between private and public space, home and work

- Access to digital tools and technological literacy

- Access to water

- Formal employment

These conditions are common in the North, and in the elite neighborhoods in the South. A large portion of the population of the Global South has to deal with:

- Reduced, shared, and unaffordable housing (informal and/or auto-constructed)

- Shared basic infrastructure (toilets, kitchens, water taps)

- High rates of informal employment (as a reference: informal workers represent 10% of total employment in France; in Mexico, they represent 53%).

- Citizens earn their livings in public space.

- Livelihoods depend on mobility and contact with others.

In these conditions, lock-downs and social distancing have been hard to enforce, or at most, it happened in elite neighborhoods. Technology has been hailed as a way to keep going forward while on lock-down. But access to technology is still an unaffordable luxury for many people. For example, the Mexican government announced on early August that classes would continue by TV. In this same context, home office is not possible for many, so people still have to go to work, and many others have lost their jobs, forcing them during this crisis to informal employment (meaning, contact with people and the public space).

Life in the public space didn’t stop. It continued…with masks and gloves, amidst violence from common and organized crime, and from law enforcement.

For these populations that don’t exactly fit into the three-act structure we saw previously, COVID-19 didn’t reveal new vulnerabilities. It intensified those that were already there.

It is our responsibility to take into account other narratives, other urban lives into our considerations of the present and the future of the pandemic.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.